Review

>

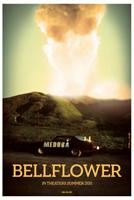

BELLFLOWER – Worth A Ticket: A Uniquely Mashed-Up Vision

Watching BELLFLOWER, you keep thinking that it’s going to resolve itself into some categorizable genre. Mumblecore romance, maybe, or low-budget apocalyptic action, or slacker comedy. But while the film sips at all of those conventions, it has a striking, oddball originality all its own: it’s the kind of picture that makes the term “festival movie” look good.

Bellflower, which premiered at Sundance, is the brainchild of Evan Glodell, who wrote, produced, directed, edited, and starred in the film. In his spare time, he modified the digital cameras used to photograph the movie in order to ensure a customized look, and created the unique vehicles that form part of the plot. (He had a bit of help on some of these duties.) The entire budget of the film was reportedly $18,000, which wouldn’t pay for a single CG shot in some Hollywood blockbusters.

All of this hard work and thrift wouldn’t pay off, though, if the picture weren’t dramatically compelling, which for the most part it is. The protagonists are Woodrow (Glodell) and Aiden (Tyler Dawson), friends from the midwest who share a house in one of the nether regions of LA. The two share a pastime that’s also an obsession: having devoured Mad Max, they want to create working artifacts that would fit the movie’s apocalyptic universe. Visions of the end of the world dance in their heads, and make them very happy. They put together their own working flame-thrower, and their dream is to create a car they call the Medusa, complete with flame-belching exhausts and video surveillance cameras whose views can be watched from the front seat. The two guys have a thriving if somewhat odd bromance.

As will happen in the movies, a woman changes everything. Milly (Jessie Wiseman) has an extremely gross meet-cute with Woodrow, and on their first date, they set off on an impromptu trip to Texas, in answer to Milly’s challenge that Woodrow take her to the most disgusting restaurant he’s ever seen. (Their ride for that journey is a car custom-fitted with a whiskey dispenser on the dashboard, which is probably illegal but way cool.) Woodrow is fumblingly head over heels, but when Milly tells him he’d be better off not thinking of her as his girlfriend, she’s not kidding. What could fairly be called an apocalyptic case of heartbreak follows, and Woodrow’s post-apocalypse universe engulfs Milly’s best friend Courtney (Rebekah Brandes) and roommate Mike (Vincent Grashaw) as well. One of the conscious ironies of the movie is that for these characters, fantasies about packs of murderous thugs don’t faze them, but they can be utterly toppled by an ordinary bad romance.

As will happen in the movies, a woman changes everything. Milly (Jessie Wiseman) has an extremely gross meet-cute with Woodrow, and on their first date, they set off on an impromptu trip to Texas, in answer to Milly’s challenge that Woodrow take her to the most disgusting restaurant he’s ever seen. (Their ride for that journey is a car custom-fitted with a whiskey dispenser on the dashboard, which is probably illegal but way cool.) Woodrow is fumblingly head over heels, but when Milly tells him he’d be better off not thinking of her as his girlfriend, she’s not kidding. What could fairly be called an apocalyptic case of heartbreak follows, and Woodrow’s post-apocalypse universe engulfs Milly’s best friend Courtney (Rebekah Brandes) and roommate Mike (Vincent Grashaw) as well. One of the conscious ironies of the movie is that for these characters, fantasies about packs of murderous thugs don’t faze them, but they can be utterly toppled by an ordinary bad romance.Bellflower doesn’t always make sense, and it’s got some considerable flaws–it falls into the mumblecore trap of dialogue that tries so hard to be “real” that it only draws attention to itself, some of the secondary characters are seriously undeveloped, and and at one point there’s a fantasy sequence so long and intense that the reveal feels like a cheat. But it’s completely unpredictable, and there’s never a moment that isn’t fascinating to watch. Joel Hodge’s cinematography, using those custom cameras, plays with the focus, isolating characters amid blur or preserving dirt on the lens; there’s also experimentation with the exposure levels of the images that makes landscapes ominously flat or bright. The actors, who generally have little screen experience, give strong performances, and their presence, along with the increasingly rapid pace of the editing, make for a gripping story with genuine suspense and surprise.

Bellflower is a discovery that’s impressive not because it was done on the cheap or has some technical tricks up its sleeve, but because it uses its resources in the service of an involving (if sometimes unpleasant) vision It’s exactly what an “independent film” is supposed to be.