1.3. 0.9. 1.4. 1.1. 0.7. 1.2. 1.3. 1.2.

Those are, respectively, the most recent Live + Same Day ratings for Quantico, Grandfathered, Code Black (which actually had a bump for the week thanks to a higher than usual lead-in), The Mysteries of Laura, The Grinder, The Muppets, Limitless, and Rosewood–all of which have received some version of a back-order for additional episodes beyond the season’s initial 13. (Blindspot and Life In Pieces, both boosted in a big way by their lead-ins, were comparatively robust at 1.9 and 2.2.)

Just a few years ago, ratings like this, while fine for cable, would have meant at least the danger of cancellation on any of the big 4 broadcast networks, and yet now they’re considered “hits.” What happened, and what’s going to happen next?

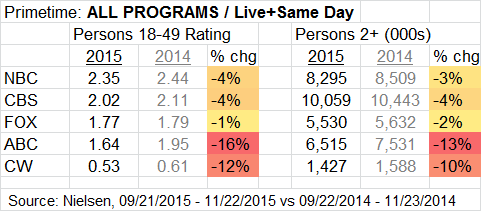

Here’s where the networks are at the end of November sweeps, having aired two solid months of original programming, compared to last fall:

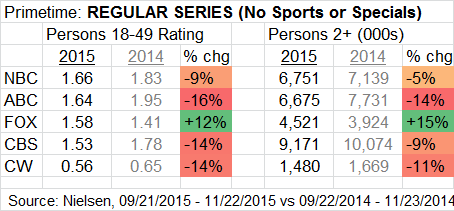

CBS, NBC and FOX are buoyed by their gigantically expensive NFL packages, which give them little if any profit, but even with those in the mix, they’re all at least marginally down. The picture becomes clearer and much more bleak if sports and event specials are removed:

(Note: The FOX increase in the regular series chart is the result of expanding Empire to a fall run. In the spring, when FOX’s numbers will include apples-to-apples comparison of two periods that include that series, the increase is likely to be largely wiped out, especially since Empire, while still huge, is now below last spring’s peak.)

Aside from FOX’s Empire bump, all the networks are down double-digits in the P18-49 demo–still the bread and butter of network revenue–except that NBC is teetering on the border of that decline. This comes after an Upfront selling season in which FOX was estimated to have rolled back its advertising rates (known as CPMs) by 2%, while NBC was up 5%, CBS was up 3-4%, and ABC was up 5-6%. (CW was up 4%, but that network has a different business model and ratings standards, so we’ll leave it to the side.) It’s difficult to fully know where the Upfronts left the broadcasters, because issues of sales volume complicate the calculations, but it’s safe to say that comparing the CPM increases to the ratings declines, all the networks (except temporarily, FOX) are making less revenue than they were a year ago.

(This is the point where we remind readers that although the networks scream about higher Live + 3 day and Live + 7 day ratings at the top of their collective lungs, and their media assistants parrot those numbers whenever prompted, they mean very little to the network bottom line. Put simply: advertisers don’t pay for DVR viewing unless viewers actually watch the commercials. We’re soon going to have a much more comprehensive post by Mitch Metcalf about the distinctions between the various ratings measurements, but the Live + Same Day numbers we and other sites post are actually the most accurate picture of the number of viewers that advertisers count in their deals with the networks. One concrete example: for a recent episode of The Walking Dead, the Live + Same Day reported rating was 6.72, but when the Same Day viewers who fast-forwarded through commercials were discounted, the number fell to 5.17. Additional viewings over the next 3 days put the gross number at 9.40, but the net “C3” number was 6.61, and when a full week was counted, the gross rating was 9.82 but the C7 figure was 6.83–less than a 2% increase over the original Live + Same Day number that was reported. And that’s for Walking Dead, with the biggest numbers on television–when talking about a show that starts with a 1.5 rating, the C7 increment wouldn’t even raise the rating by an extra tenth.)

The worse news, of course, is that the trend is going in the wrong direction for the networks. With a constantly multiplying assortment of new subscription-funded platforms offering content that’s often (at least) as high quality as that provided by the broadcasters, viewership is likely to keep slipping, and advertisers will place more and more of their resources elsewhere, especially in media that can target ads to specific viewers based on their recorded purchase and online browsing habits. (We’ll leave the Big Brother concerns about that for another day.) Network television, by comparison, is a very blunt instrument that’s always been sold on the basis that if you gather the largest total number of people, the consumers advertisers really want will be somewhere in there.

For a variety of business and political reasons, the broadcast networks are unlikely to go defunct any time in the foreseeable future (despite their occasional threats to “go cable” when they don’t get their own way). But what can they do?

All the networks are working feverishly to get viewers to watch their delayed programming online or through cable/satellite VOD services rather than on DVRs, because those media don’t permit fast-forwarding, making them more advertiser-friendly, especially as technology evolves to permit targeted ads. But while the networks boast about an ever-increasing number of viewers migrating there, they issue little hard data to back that up, making for the suspicion that the numbers are still quite low.

So the general answer is that they do the best they can. With respect to programming, this fall strongly suggested that for the most part, the networks will now be aiming at the broadcast possible audience, even if it means sacrificing younger eyeballs. Procedurals and big tent comedies are the order of the day, and they’re drawing an ever-aging audience, with Total Viewers falling more slowly than 18-49s (or rising higher in the case of FOX). Older audiences earn lower CPMs from advertisers, but there’s still money to be had from the 50+ crowd, and the networks will take what they can get. That contributes to the continued existence of shows like The Mysteries of Laura and Code Black, which over-index with that audience.

The networks will also try desperately to keep costs down, not only in reduced license fees that require the studios to take higher deficits, and through co-productions that shave traditional network rights in exchange for investment (an example is CBS’s deal with Amazon that put shows like Under the Dome on the streaming platform months faster than would otherwise have been the case), but by saving on marketing costs. This is one of the reasons more marginal shows are staying on the air–so that their networks don’t have to bear the expense of constantly launching new product. When the difference between a “hit” and a “flop” is a matter of three or four tenths of a ratings point, a lower-rated incumbent may actually be more profitable than a new show that modestly pops only at the cost of an expensive marketing effort.

In a fundamental way, though, the concept of the network broadcasting business as a standalone profit center is also changing. More and more, the networks are going to face dwindling profits and even losses as they balance their license fees against the revenues they’re able to realize from their broadcasts. The shows themselves, however, can continue to be very profitable, thanks to their ancillary value overseas, in cable and local station syndication, and especially through sales to streaming services like Netflix, Hulu and Amazon that are hungry for content. That revenue, however, goes to the studios that produce the shows and not to the networks (the question of whether it’s a better longterm strategy for the studios to sell their product to third-party streaming services for quick cash rather than retaining those rights and building their own streaming platforms can also be left for another day).

Take another look at that list at the top of this article. Every one of those back-ordered series is at least co-produced by the in-house studio wing of the conglomerate that owns the network airing it, allowing the company, if not the network itself, to share in its non-broadcast success. (Update: this morning, CBS gave a 7-episode back-order to Supergirl, which is owned by Warners, making it the exception to the rule.) The networks may be migrating toward becoming something like loss leaders for their ownership, establishing the value of a series so the company as a whole can make a profit on it. This isn’t great news for studios like Sony and Lionsgate, which have no networks of their own and will increasingly have to accept co-production deals with in-house studios in order to make sales. For the networks themselves, it means being more patient with in-house product even at the expense of middling (or worse) ratings, because in the new paradigm, building inventory for its studio to sell is critically important.

And for viewers, it likely means more seasons like this one, loaded with shows that show little interest in creative daring and rely on vanilla content, yet stay on the air unless they utterly crater. That will likely mean even more of a breakdown in the traditional habit of considering broadcasters the default choice for viewing. And the cycle will continue, moving not so much toward a Dr Strangelove-ian Doomsday Device as toward an end that comes not with a bang, but with a whimper, as NBC, CBS, ABC and FOX become acronyms no more influential or powerful than those for a dozen other providers of content.

Related Posts

-

Weekly & Season to Date Network Ratings

Projected weekly network ratings in prime time (based on four days of official nationals and three days of fast nationals). CBS racks up another victory (helped by an hour of The Masters spilling into prime time Sunday). Weekly Rating Apr 8-14 18-49 Rating vs Last Year CBS 2.44 -0.6% Down…

-

THE SKED: CBS

>Thoughts on CBS’s Schedule (and Our Predictions)CBS COMEDIESCBS DRAMASABC ANALYSIS CBS ANALYSIS NBC ANALYSIS FOX ANALYSIS CW ANALYSIS

-

Broadcast Season to Date Rankings

SEASON TO DATE through eight full weeks (54 nights of official ratings and 2 nights of adjusted fast nationals through Sunday, November 18, 2012): NBC is averaging a 2.79 adult 18-49 rating in prime time (up 14% from the same period last year). CBS is in second place with a 2.34…

-

Weekly & Season to Date Network Ratings

Projected weekly network ratings in prime time (based on four days of official nationals and three days of fast nationals). Weekly Rating Apr 1-7 18-49 Rating vs Last Year CBS 2.68 -4% Up from 2.25 last week NBC 1.67 +7% Up slightly from 1.64 last week FOX 1.64 -27% Up…

-

Broadcast Season to Date Rankings

SEASON TO DATE through nine full weeks (60 nights of official ratings and 3 nights of adjusted fast nationals through Sunday, November 25, 2012): NBC is averaging a 2.84 adult 18-49 rating in prime time (up 23% from the same period last year). CBS is in second place with a 2.29…